14

les collections aristophil

Texte :

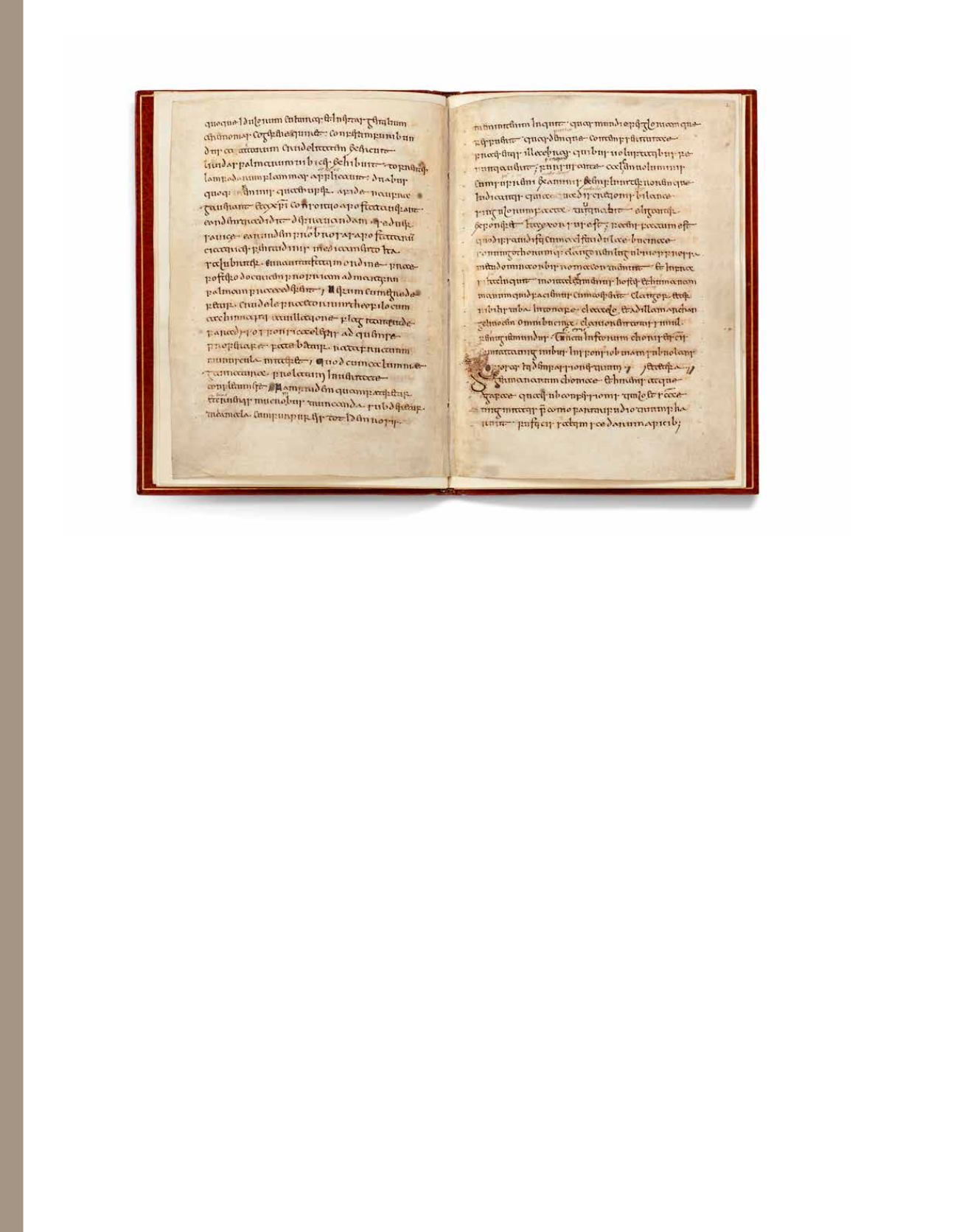

Les manuscrits de ce texte sont rares. Il s’agit ici du témoin le plus

ancien conservé, copié au cours du siècle qui suit la mort de l’auteur,

antérieur au manuscrit de Würzburg (M.th.f.21) également du IX

e

siècle

(Gwara,

Aldhelmi

, 2001, p. 85). Le manuscrit d’où proviennent les deux

présents feuillets est sans doute à l’origine de toute la tradition textuelle

en Angleterre avant la conquête. Les feuillets contiennent une partie

des chapitres 47 et 49-50 relatives aux saintes Scholastique, Christine

et Dorothée (fol. 1) et Eustochius, Demetria, Paula et Blesilla, ainsi

que les passages relatifs aux passions des martyrs Chiona, Irène et

Agape (fol. 2). Les leçons de ces feuillets relèvent de la « class I » de

Gwara et les variantes conservent des particularités orthographiques

remontant à l’orthographe d’Aldhelm lui-même (Gwara,

Aldhelmi

,

2001, p. 93 : [the minor variations in the text] “preserve orthographical

peculiarities probably traceable to Aldhelm’s own spelling”).

Ces feuillets contiennent de surcroît 17 gloses interlinéaires avec 20

mots en anglo-saxon. T.E. Marston évoque d’autres témoins de ce

manuscrit conservés à Yale : “For centuries such manuscripts have

been avidly sought by English collectors and scholars, and their

scarcity is legendary” ; “Any manuscript which preserves so much as

a phrase of original Anglo-Saxon is a noble relic” (Collins, 1976, p. 13).

C’est à travers des manuscrits comme celui-ci que l’on est à même de

reconstituer la genèse et prémices de la langue anglaise. La plupart des

manuscrits contenant des éléments d’anglo-saxon (fragments, gloses

éparses) sont conservées dans des collections à Londres, Oxford et

Cambridge. En mains privés et hors Grande-Bretagne, les manuscrits

contenant des éléments d’anglo-saxon n’existent pratiquement pas.

L’enquête pionnière de Ker sur les manuscrits contenant des éléments

linguistiques en anglo-saxon recense en 1957 neuf manuscrits en mains

privées. Un témoin est perdu, et tous les autres ont depuis intégré

des collections publiques. D’autres feuillets provenant du présent

manuscrit démembré ne présentent pas de gloses en anglo-saxon.

La datation de ces gloses au X

e

siècle permet d’affirmer qu’elles

appartiennent aux témoins les plus anciens : seul environ 1/5

e

des

manuscrits en ancien anglais (Old English) sont datables avant le XI

e

siècle. Signalons un mot trouvé dans ce seul manuscrit :

clangetug

(fol. 2r, ligne 13), qui renvoie au « tumulte des Goths ».

Text:

Manuscripts of the text are rare. This is the earliest witness to the

text, written within a century of the author’s death, and “predates the

Würzberg copy [Würzberg, M.th.f.21, the only other ninth century

witness] by at least a generation” (Gwara,

Aldhelmi

, 2001, p. 85). It

is almost certainly responsible for the entire textual tradition in pre-

Conquest England. The leaves here comprise parts of chs. 47 and

49-50 on SS. Scholastica, Christina and Dorothy (fol. 1) and Eustochius,

Demetria, Paula and Blesilla, and the Passions of the Diocletian martyrs

Chiona, Irene and Agape (fol. 2). Their readings are of Gwara’s “class I”,

and the minor variations in the text “preserve orthographical peculiarities

probably traceable to Aldhelm’s own spelling” (Gwara,

Aldhelmi

, 2001,

p. 93).

These leaves preserve 17 Anglo-Saxon interlinear glosses with 20

words. “For centuries such manuscripts have been avidly sought

by English collectors and scholars, and their scarcity is legendary”

(T.E. Marston about the Yale leaves of the present manuscript). “Any

manuscript which preserves so much as a phrase of original Anglo-

Saxon is a noble relic” (Collins, 1976, p. 13). English is now as near to

a universal language as there has ever been, and its earliest history

can be reconstructed almost exclusively from fragments and glosses.

Almost all are in the great national collections in London, Oxford and

Cambridge. In private hands, or outside Britain, pieces of the Anglo-

Saxon language hardly exist.

Ker’s monumental survey of manuscripts containing Anglo-Saxon

lists nine in private hands in 1957. One is now lost; all the others are

now in institutional ownership. Many other leaves from the present

manuscript have no Anglo-Saxon glosses; the leaves here have

seventeen glosses with twenty words in total. Ker’s dating of these

to the tenth century puts them among the earliest records of that

language: only about a fifth of extant Old English manuscripts are

older than the eleventh century. One word here is unique:

clangetug

(fol. 2r, line 13), referring to the tumult of the Goths.

Decorated initial:

The insular combined-initial clearly echoes the interlocking “Li” initials

opening “Liber” in early English Gospel Books (cf. Alexander,

Survey

of MSS Illuminated in the British Isles, 1, Insular MSS.,

1978, pls. 52, 123

and 125), but closer parallels for the sweeping fishhook-like ascenders,