14

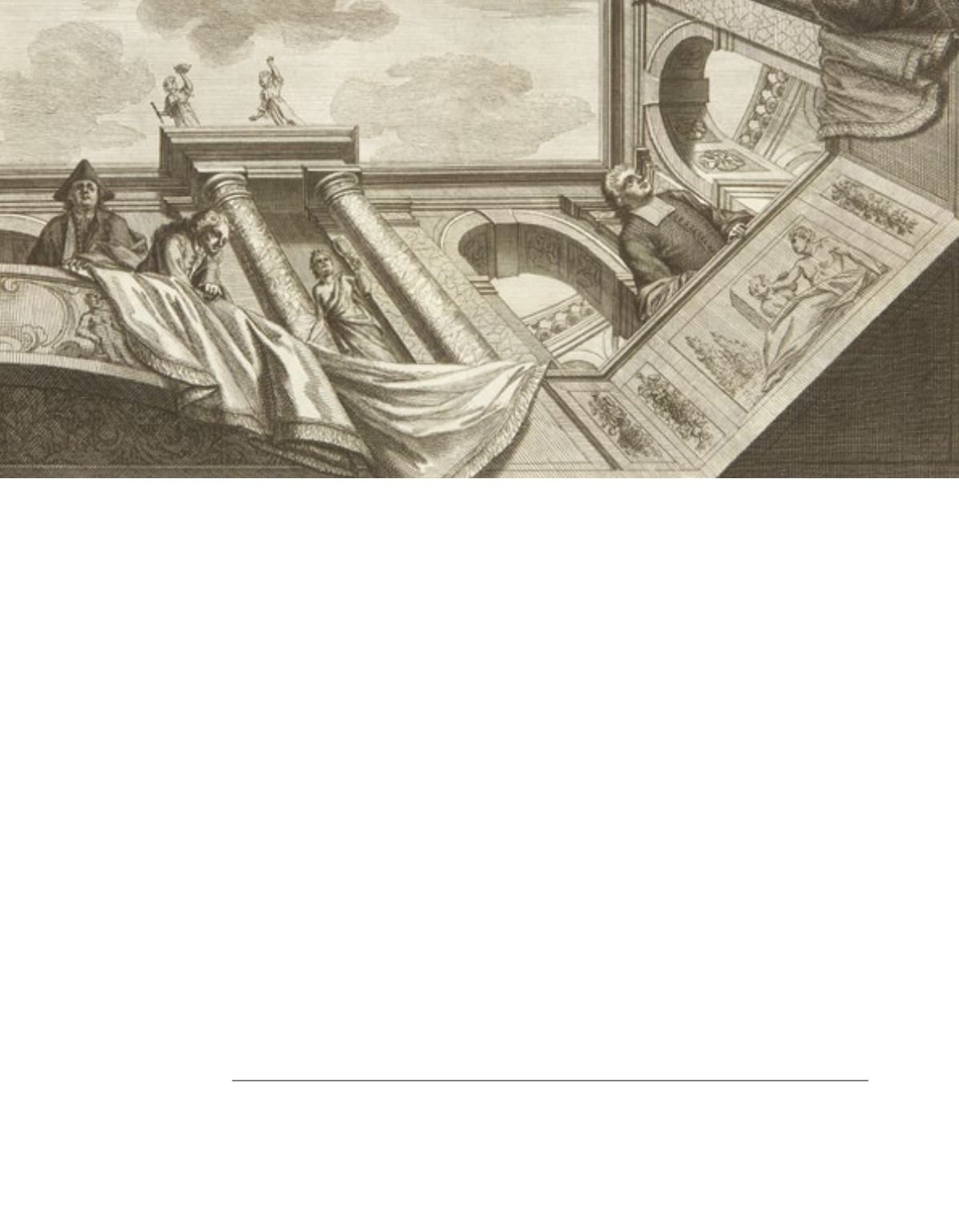

A related facet of perspectival design involved a kind of natural magic in which wonder and

astonishment were the prime ends in view. Some of the perspective books in themselves cultivated

the “wow” factor, such De Vries’s elaborately confected scenes of buildings in perspective.*

39

In 17

th

century Holland we also encounter “perspective boxes”, optical peepshows which beguile us with a

precocious form of virtual reality – the most famous of which is the elaborately staged box of optical

tricks by Hoogstraten in the National Gallery, London. Perhaps the most wondrous of the effects were

created by anamorphosis, in which an image projected from an extremely shallow angle of view outside

one lateral edge of the picture plane was reconstituted into a naturalistic illusion when viewed from

the corresponding position.*

40

In 17

th

century Rome, Maignan and Niceron (whose copy of Dürer is in

the present collection) used the anamorphic technique to conjure up a visionary image of St. Francis of

Paola in a corridor in Sta Trinità dei Monti.*

41

The title of Niceron’s own learned and splendid treatise,

Curious Perspective or the Artificial Magic of Marvellous Effects, perfectly captures the spirit of the

enterprise*

42

. Generally with such extreme illusions, some of which involved cylindrical and conic

mirrors,*

43

entertainment rather than devotion was involved.

As expanded public access to visual entertainments developed in the later 18

th

and 19

th

centuries, we

encounter miniature pop-up theatres constructed from card, mirroring the optical delights of full-

scale scenery. Only a small proportion of them survive. The present collection contains a fine set of

Theatres d’Optique, together with a Polyrama Panoptique, which used light effects to enhance views

of Paris, and a Telorama tour of the Rhine. The “scientific” titles are designed to enhance the viewers

participation in a privileged “modern” experience.*

44

By the time we reach the 18

th

and early 19

th

centuries we find on one hand books of sober and technical

geometry, projective and descriptive (dealing with the nature of 3-D forms rather than their optical

appearance), which moved beyond the concerns and grasp of most painters, and were not designed for

visual appeal.*

45

The teaching of perspective at a technical level also persisted in military academies. On the

other hand we have publications of more affordable text-books, neatly illustrated and parading manageable

techniques. The more pedagogic of the books are aimed not least at the kind of well-bred amateurs who

*

39

243, 384, 389

*

40

223, 249-251

*

41

223

*

42

249-251

*

43

15-16, 364

*

44

289, 351-353, 354-355

*

45

159, 181, 204