11

There are also quite elaborate optical machines in which some kind of sighting device is angled towards

a given point or contour on an object, while a mark-making component moves across what is to be the

picture plane registering the optical location of the point or contour*

15

. Dürer was the earliest master

of such things.*

16

Such “perspectographs” were indeed made and some examples have survived from

later periods. But they seem generally to be more in the nature of prestigious devices for demonstration

purposes rather than serving the utilitarian needs of practicing painters.

The making of such fine technical instruments became a matter of pride from the 16

th

century onwards.

We also find some illustrations of the camera obscura, the “dark chamber” with an aperture in one

of its sides that served to create an inverted image of what lay illuminated outside the “camera” (with

or without the assistance of a lens).*

17

The “camera” features somewhat less frequently than we might

expect, given its likely use by Dutch and Dutch-influenced artists from the 17

th

century onwards. Most

authors are concerned with geometrical rectitude than the direct transcription of raw nature.

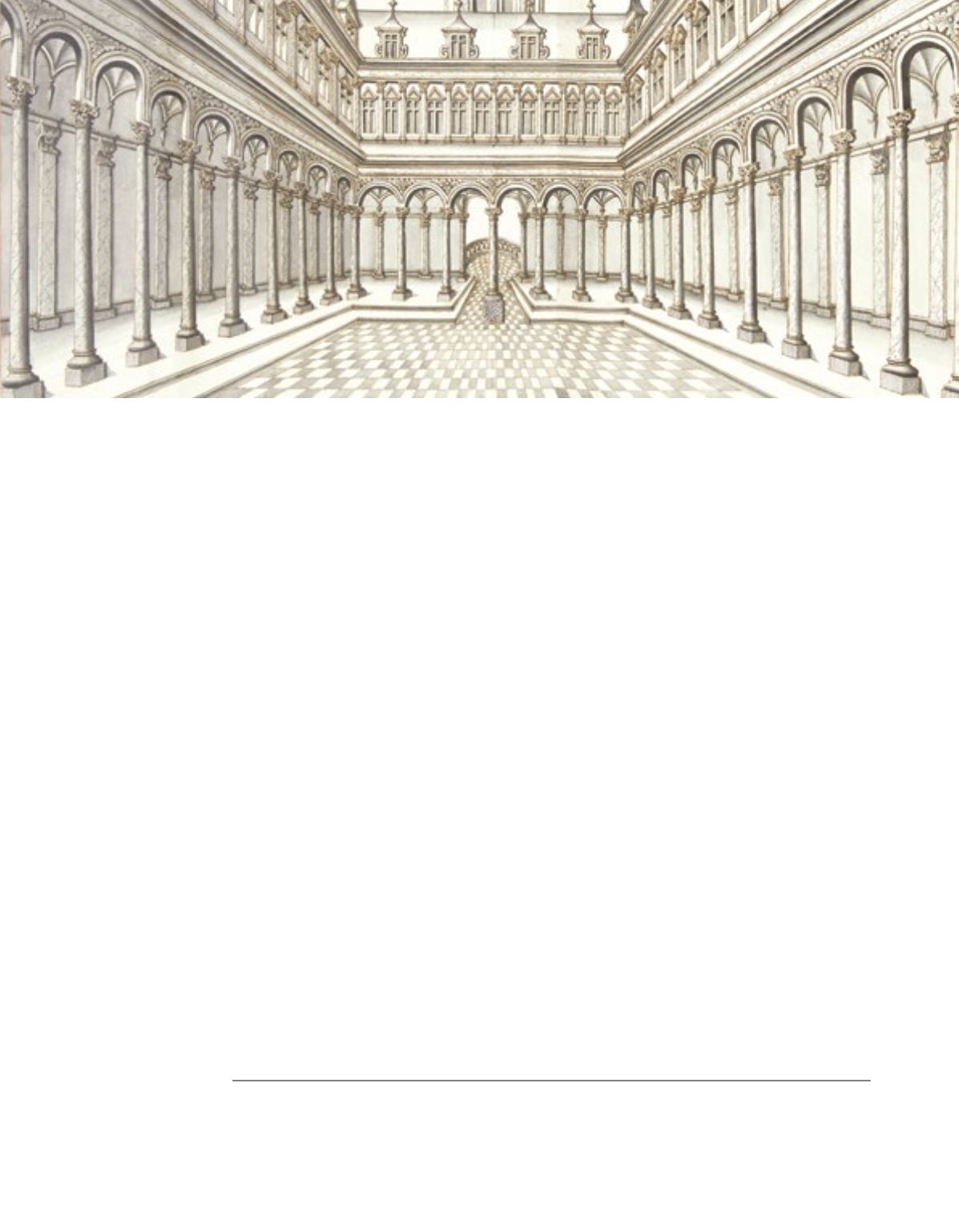

Our archetypal book may well conclude with worked examples closer to the desired paintings of

subjects that were current at the time and place of the publication. The Italians and Dutch stand

at the opposite end of the scales. Italian 16

th

century and Baroque treatises are likely to emphasise

grand architectural constructions in an all’antica manner and heroic figures, especially as projected

illusionistically on to ceilings, vaults and domes. Such architectural projections are represented most

spectacularly by Pozzo.*

18

The Dutch, unsurprisingly, follow a more empirical bent with constructions

of domestic rooms containing clearly scaled furniture and inhabitants*

19

, urban views, lofty church

interiors, and landscapes with perspectival motifs such as rows of trees and artfully placed boats on

calm waters.

The Vroom collection allows us to chart the diffusion of the perspective book, from its origins

in Italy, closely followed by France, where the earliest illustrated treatise was published in 1505,

the eccentric and pioneering treatise by Jean Pelerin (Viator).*

20

Germany, an important cradle

of northern humanism, followed with the supremely important Instruction in Measurement... by

Dürer in 1525.*

21

Thereafter we witness the spread to Holland, Belgium, Spain, Portugal and eventually

to 18

th

century Britain, where the belated perspectivists associated themselves with the international

prestige of Newton. While many of the treatises were published in the vernacular, Latin continued to

be used on an international basis. Dürer’s book, translated into Latin by Camerarius in 1532, served

to bring the artist’s vernacular geometry into scholarly circulation.*

22

*

15

58, 95, 119, 141, 256, 320, 372

*

16

112-118

*

17

200, 318

*

18

19, 242, 293, 297

*

19

177

*

20

26-27

*

21

112-118

*

22

115