35

britannica - americana

Young Men’s Magazine,

dont on ne connaît plus que trois : le premier

est au Musée Brontë, le second, composé de trois pages a été vendu

aux enchères chez Christie’s en décembre 2009, et celui-ci.

Les

Juvenilia

des enfants Brontë sont d’une importance exceptionnelle,

annonçant et éclairant les œuvres de l’âge adulte. Dans le triste

presbytère de Haworth dans le Yorkshire, après la mort de leur

mère, la triste expérience du pensionnat, et la mort des deux filles

aînées, les quatre enfants survivants sont éduqués à la maison, où

ils peuvent laisser libre cours à leur imagination sans borne, nourrie

par le libre accès à la bibliothèque du père. Ils se créent, à partir

d’une boîte de petits soldats, l’univers imaginaire de

Glass Town

.

Chaque enfant adopta un soldat, et lui attribua un nom de héros :

Wellington pour Charlotte, Napoléon pour Branwell ; Emily et Anne

choisirent des noms d’explorateurs : Edward Parry et William Ross.

Les enfants inventèrent alors un univers, une « confédération », dans

laquelle chacun des quatre enfants avait son propre royaume articulé

autour de son héros. La conception de leur monde et les aventures

de ses habitants tirent abondamment leur source du

Blackwood’s

Magazine

, auquel leur père était abonné. En 1829, les deux aînés,

Charlotte et Branwell, commencèrent à rédiger des histoires se

déroulant dans leur royaume imaginaire : Branwell commença avec

le

Branwell’s Blackwood Magazine

, à l’imitation de leur magazine

favori, puis Charlotte écrivit six numéros du

Blackwood’s Young Men’s

Magazine

entre août et décembre 1829. Au mois d’août de l’année

suivante, elle commença une « seconde série » au titre abrégé :

Young

Men’s Magazine.

Le magazine est composé de récits de voyage

et d’aventures, souvent sous la forme d’échanges épistolaires avec

divers correspondants, de récits plus longs en plusieurs épisodes, de

poèmes, de « Conversations », et même d’annonces et de critiques de

livres (fictifs) et de peintures. Ces différentes œuvres sont écrites par

des personnages imaginaires, et distribuées par un libraire imaginaire.

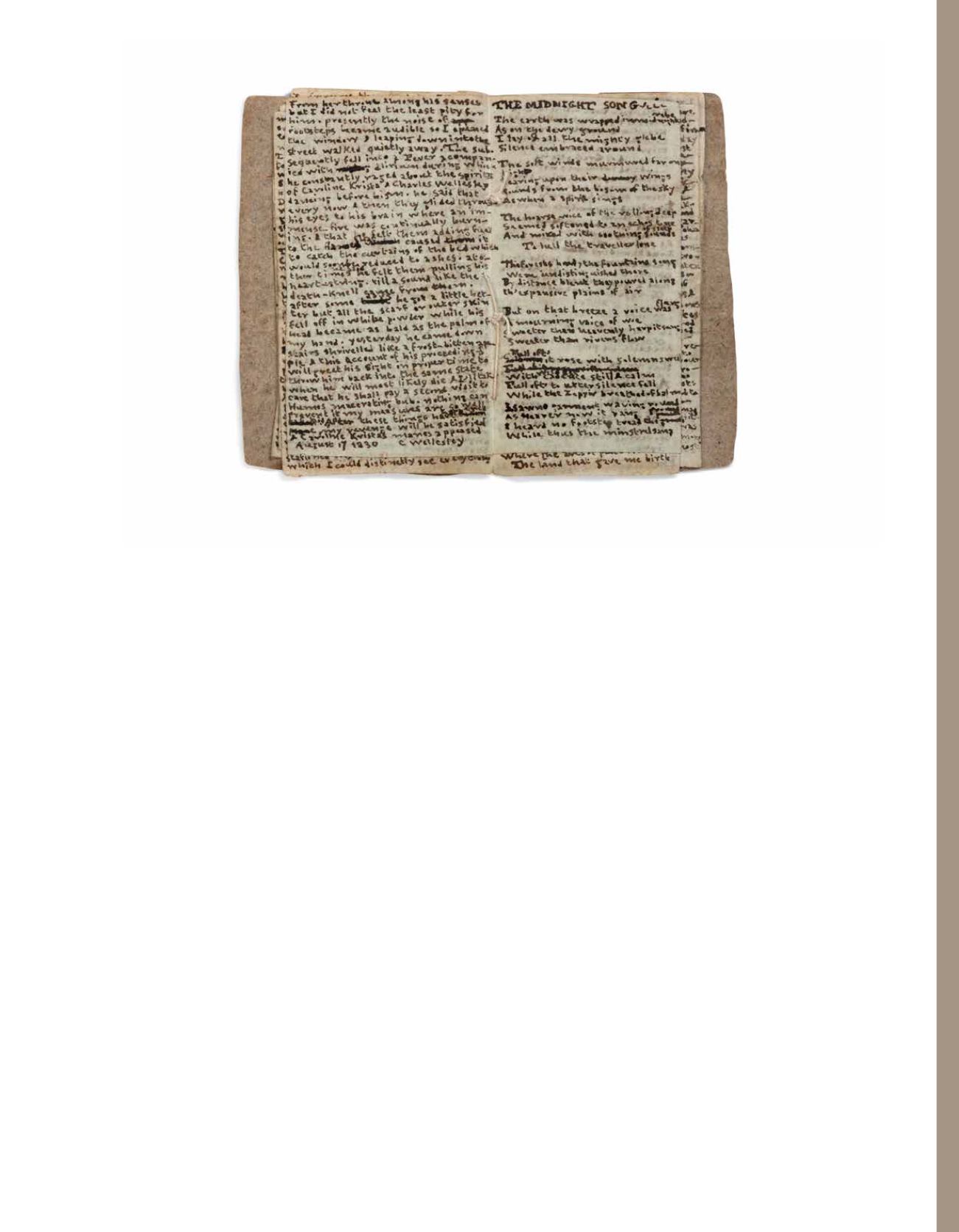

« Une montagne d’écriture, sur un espace incroyablement petit »

,

commenta Mrs Gaskell à propos des écrits de jeunesse de Charlotte.

Sa taille minuscule est la plus extraordinaire caractéristique de ce

manuscrit, qui contient plus de 4000 mots accumulés sur seulement

19 pages de format 3,5 x 6,1 cm, d’une écriture très dense et serrée,

pour donner l’effet d’un magazine imprimé en imitant les caractères

d’imprimerie. La taille de ce magazine s’explique aussi par la possibilité

de le cacher facilement.

Brontë juvenilia is of unusual importance as their childhood empires of

the imagination loom so large in our understanding and appreciation

of their mature works: generations of readers have been moved by

the thought of these four extraordinarily gifted children conjuring up

wonderful worlds together in their lonely Yorkshire parsonage. In their

father’s words: “As they had few opportunities of being in learned

and polished society, in their retired country situation, they formed a

little society amongst themselves – with which they seem’d content

and happy.” (Rev. Patrick Brontë to Mrs Gaskell, 20 June 1855). This

solidarity was certainly fostered by the relatively isolated position of

Haworth, but it was engendered by family tragedy. Their mother had

died when Charlotte was five and her youngest sister Anne only one,

and the only extended period spent by any of the siblings outside the

family had been when the four oldest girls (including Charlotte and

Emily) had been sent to the Clergy Daughters’ School at Cowan Bridge

in Lancashire. The brutal, uncaring and unsanitary regime had left the

girls half-starved and susceptible to disease, leading to the death of

Charlotte’s two elder sisters Maria and Elizabeth (Charlotte’s fury at

the school finally found expression in her depiction of it as Lowood

School in Jane Eyre). After this traumatic experience the four surviving

children were educated at home, their unfettered imaginations fed

by free access to their father’s library.

The world of

Glass Town

, the first expression of the incredible

imaginative community at Haworth, had its origins in a gift of toy

soldiers:

« Papa bought Branwell some soldiers from Leeds. When Papa came

home it was night and we were in bed, so the next morning Branwell

came to our door with a box of soldiers. Emily and I jumped out

of bed and I snatched one up » and exclaimed, ‘This is the Duke of

Wellington! It shall be mine!’... (Charlotte Brontë,

The History of the

Year

, 12 March 1829).

Following Charlotte’s lead, each of the siblings took one soldier as

their own and named them for a hero: Branwell chose Napoleon in

a riposte to Charlotte’s Wellington, whilst the younger sisters Emily

and Anne named theirs for the explorers Edward Parry and William

Ross. The children assembled a world – a “confederacy”, in which

all four siblings had their own realm – around these characters.